“Packed with humorous scenes, but it engaged the audience to reflect on the identity of a Malay.” —Nurmaya Alias, Berita Harian, on The (Assumed) Vicious Cycle Of A (Melayu) Youth (translated from Malay)

“Assumptions and stereotypes are cheekily shaken up in this energetic play” —Akshita Nanda, The Straits Times Life, on The (Assumed) Vicious Cycle Of A (Melayu) Youth

There is a new king of the jungle! While the previous lion kings ascended the throne via their royal lineage, the animals of the jungle have broken with centuries of tradition, and democratically elected a new king of a more peaceful nature.

WAN BELANTARA: Enjet-Enjet Semut (KING OF THE JUNGLE: As the Ants Go Marching In) tells a story of an army of ants embarking on a journey to send gifts and tributes to their new king. The ants believe that it was their large numbers that contributed to this landmark election of a new king, and that they were the ones who brought change to the administration of the jungle. Now, with a different type of animal elected as the king, it is a time for a celebration.

Directed by Saiful Amri and written by Anwar Hadi Ramli, WAN BELANTARA: Enjet-Enjet Semut draws inspiration from Farid ud-Din Attar’s poem Conference of the Birds and weaving between fables and well-known stories from the Malay Annals, such that of Hang Tuah and Hang Jebat. WAN BELANTARA: Enjet-Enjet Semut examines what would make the people be loyal to, or betray a leader, and what injustices may drive people to mengamuk (run amok).

RELATION TO QUIET RIOT

WAN BELANTARA: Enjet-Enjet Semut subtly addresses the issue of blind obedience or loyalty, which seems predominant in various areas of Singapore society.

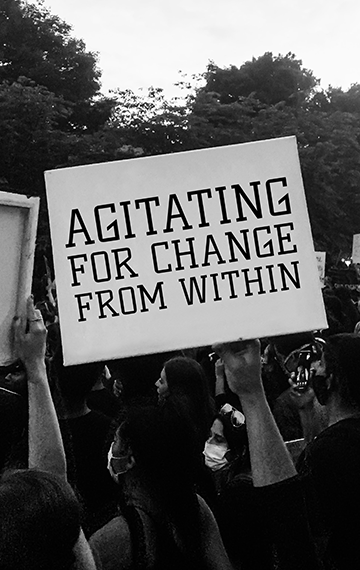

Here, it is illegal to hold a demonstration or march without a permit to address an oppressing issue. Rioting is a definite no-no in Singapore. In contrast, loud and massive demonstrations are common elsewhere in the Malay world. We know how they can overthrow administrations. We also know of some demonstrations that escalated into riots and people running amok.

In certain historical accounts, there are stories of Malay persons running amok. Dictionaries cite the first use of the word “amok” in 1865-70 from the Malay word amuk, attributing its origins to behaviour occurring especially in Malay culture in Southeast Asia.

Do we need to mengamuk (run amok) to make our voices heard? Do we need to resort to violence, or even killing, to uphold a perceived justice? Or are there other ways of waging quiet riots as we demand change for the betterment of our society?

With the support of Hong Leong Foundation and Malay Language Learning and Promotion Committee.

Preferred Projector Partner: Epson Singapore

“Packed with humorous scenes, but it engaged the audience to reflect on the identity of a Malay.” —Nurmaya Alias, Berita Harian, on The (Assumed) Vicious Cycle Of A (Melayu) Youth (translated from Malay)

“Assumptions and stereotypes are cheekily shaken up in this energetic play” —Akshita Nanda, The Straits Times Life, on The (Assumed) Vicious Cycle Of A (Melayu) Youth

There is a new king of the jungle! Previous lions became kings because of their royal lineage. The animals of the jungle have broken with centuries of tradition. They have elected a new king of a more peaceful nature.

WAN BELANTARA: Enjet-Enjet Semut (KING OF THE JUNGLE: As the Ants Go Marching In) tells a story of an army of ants. They are going on a journey to send gifts and tributes to their new king. The ants believe that their large numbers contributed to this landmark election of a new king. They think they brought change to the administration of the jungle. Now, with a different type of animal elected as the king, it is a time for a celebration.

WAN BELANTARA is directed by Saiful Amri and written by Anwar Hadi Ramli. It draws inspiration from Farid ud-Din Attar’s poem Conference of the Birds. It also weaves between fables and well-known stories from the Malay Annals. These include that of Hang Tuah and Hang Jebat. WAN BELANTARA examines what would make the people be loyal to, or betray a leader. It also looks at what injustices may drive people to mengamuk (run amok).

RELATION TO QUIET RIOT

WAN BELANTARA: Enjet-Enjet Semut subtly addresses the issue of blind obedience or loyalty. This seems predominant in various areas of Singapore society.

Here, it is illegal to hold a protest. You cannot march to address an oppressing issue without a permit. Rioting is not allowed in Singapore. In contrast, loud and massive protests are common elsewhere in the Malay world. We know how they can overthrow administrations. We know of some protests that became riots with people running amok.

In certain historical accounts, there are stories of Malay persons running amok. Dictionaries cite the first use of the word “amok” in 1865-70 from the Malay word amuk. Its origins can be from behaviour occurring especially in Malay culture in Southeast Asia.

Do we need to mengamuk (run amok) to make our voices heard? Do we need to resort to violence, or killing, to uphold a perceived justice? Or are there other ways of waging quiet riots as we demand change for the betterment of our society?

With the support of Hong Leong Foundation and Malay Language Learning and Promotion Committee.

Preferred Projector Partner: Epson Singapore